The Autochrome

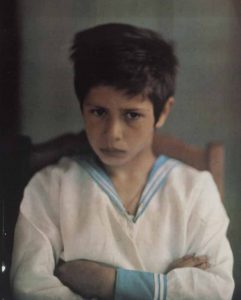

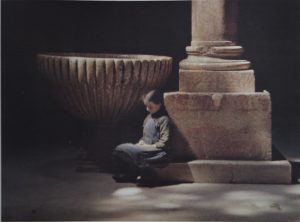

Part of a steroscope Autochrome by Leonid Andreyev

This Autochrome essay was my final essay on my HNC Photography Course – I gained a Distinction for the whole course, which entailed gaining a Distinction on each of ten modules.

In the context of this Autochrome essay what do we understand ‘colour photography’ to encompass?

- Does it refer to a transparent image that can’t be duplicated or printed and can only be viewed by projection or with special viewers

- Does it refer only to a physical colour print that we can hold in our hands, that can be duplicated, enlarged and be viewed by many people at one time?

Photography has often been described as the pencil of nature and its direct translation means drawing with light. Sir Issac Newton discovered that light is made up of the colours of the spectrum, so one could draw the inference that any technology that worked with light might and should include colour.

Today’s colour photography

We are now able to produce both colour transparency images which can be duplicated, printed and projected at a larger scale than anything available at the turn of the twentieth century. We can also produce brightly coloured images on paper at a variety of scales on different stocks, so I would suggest that ‘colour photography’ can include both transparency and paper prints.

When the first photographs hit the public arena in 1839, they were monochrome tones rather than natural colours, disappointing many.

‘How could a process that captured the forms of nature with such exquisite detail, fail so dismally to record its colours2?’

And so ‘the race was on for colour3‘.

Early attempts

An initial response was to hand colour prints and some portrait painters, struggling to survive after the invention and rise of photography, learnt how to add colour to daguerreotypes. While this produced a pleasant effect, it very much depended on the skill of the retouch artist and was time-consuming and not cost effective.

One early colour attempt was made in 1840 by Sir John Herschel who was able to register colours on paper with light-sensitive silver chloride, but was not able to fix them and eventually they darkened. However, he was able to bring colour, albeit one colour, into a photographic image with his invention of the cyanotype in 1842.

The cyanotype

This was based on a blue pigment called Prussian Blue, which was used by painters and is what we know now as a ‘blueprint’. Other ways that photographers introduced colour into their images was through the use of different coloured printing stock. These were called Autotype Pigment Papers and they were actually carbon tissues, used by amateur and professional alike. Apparently, the company is so popular it is still operating today.

First successful experiment

James Clerk Maxwell’ additive first colour attempt – a tartan ribbon – print of this was created by the Vivex process in the 1930s

The first relatively successful ‘additive’ colour experiment was that of James Clerk Maxwell who, using black and white negatives shot through respective red, green and blue filters, produced a famous image of a tartan ribbon and rosette.

This produced a recognisable colour image. However ‘the difficulties of achieving the much-desired colour on paper by the additive process4’, meant that a print was not produced from the negatives until the 1930s by the Vivex process.

Other attempts to create permanent colour images

Other processes that were attempted included:

- a filter colour line screen process invented by Joly

- a mosaic screen created by McDonough

- a one-shot colour camera using triple negatives called Heliochromy.

- In 1869 Du Hauron demonstrated ‘subtractive’ photographs on paper, but due to the insensitivity of the materials of the period, the colour balance was incorrect.

- F. E. Ives created an additive system called Kromskop similar to Maxwell’s process which exposed three separate black and white negatives on a single plate through blue/violet, green and red filters. Three glass positives were made through contact printing, cut and then viewed through the Kromskop viewer. Again the image would prove extremely difficult to print on paper.

- Gabriel Jonas Lippman’s direct interference system. This was neither additive or subtractive, but worked through the creation of interference patterns between light waves. This process used mercury to reflect light into the photographic emulsion, similar to our modern hologram technique.

Inspiring the Lumière brothers

McDonough’s earlier mosaic screen provided the impetus and inspiration for the Lumière brothers’ offering, a process that would stun the photographic community, sweeping the world with ‘colour fever5’. This process was the Autochrome process.

The Autochrome process

The Lumières were already involved in the photographic world, making strides in cinematography and creating ‘an easy to use, affordable “dry” black and white plate called ‘Etiquetter Bleue’6’. This proved very successful and provided enough finance for them to explore and experiment with colour photography, a quest which lasted 14 years. The company eventually became the largest photographic manufacturer in Europe.

Another use for ‘the Humble Potato’

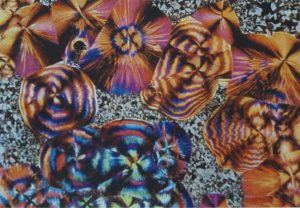

Microscopic grains of starch from the ‘Humble Potato’ were used to create a mosaic screen on a glass plate. The grains were dyed three different colours: blue/violet, vermilion/orange and green and then mixed together in roughly equal proportions.

They were then spread extremely thinly on a glass plate that had been spread with varnish. The tiny spaces between the grains were filled with carbon black.

The new and more sensitive fine-grained, panchromatic silver bromide emulsion was spread over the whole plate. Finally, the plate was subjected to a very high pressure to ensure that the grains became very thin and transparent.

Exposing the new photographic plate

To expose the plate it was placed in the camera with the emulsion furthest away from the lens (the opposite way to how plates were normally exposed). Light then passed through the colour mosaic screen before registering on the emulsion.

A yellow filter was placed over the camera lens to balance the over blue sensitivity of the plate. Processing entailed developing the negative image, removal of the developed silver, then the development of the residual positive image. The actual development itself in total darkness was difficult for photographers used to black and white printing.

Untitled, Rudolf Dūhrkoop

Some drawbacks of the new process

- Plates were a lot slower than the black and white plates, as filling the gaps between the grains ‘reduced the effective speed of the plate7’.

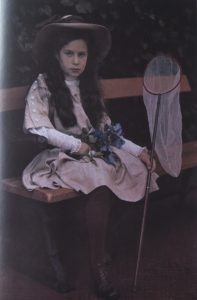

- Subjects had to remain still for at least a second, taking photography back to its early days of rigid poses and no movement.

- Photographers had to become much more conscious of elements and colours within a possible image, selecting and rejecting items to become part of the composition, and staging images rather than allowing the action to occur naturally.

- Often the starch grains would clump together showing particularly in large areas of colour such as skies, although on a positive note it did help create the very ‘dreamy’ quality of the process.

- Plates were very fragile meaning that many did not survive.

- The process produced a positive transparency which at that point in time was unable to be duplicated or direct colour prints made from it.

- Difficult for large numbers of people to view the transparencies at the same time, making exhibition problematic.

- Professional photographers such as Stieglitz, Steichen and other Pictorialists and Photo-Secessionists felt the process allowed little leeway for artistic ‘tweaking’ (unlike black and white photography), giving ‘the operator no right to call himself their creator8’.

- This was one of the main reasons why many eventually stopped using the process, including Stieglitz, whose enthusiasm ‘would last only about a year9’. The only way creative input was possible was during the development process, which Steichen became proficient at.

- Cost was also an issue, with plates being supplied in boxes of four rather than the usual twelve as they were so expensive to produce.

- Exposure. No consistency in the sensitivity of the plate which made it difficult to judge the exposure time. This was improved later in the life of the autochrome process.

The positive aspects

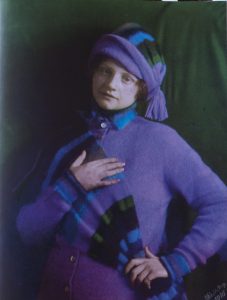

- It produced ‘luminous and lush10’, ‘distinctive colour quality11’, with an ‘unreal shimmering Impressionist colour cast and an atmospheric depth12’.

- It produced Autochromes that were ‘lyrical and evocative13’ with ‘inherent luminous beauty and dream-like quality14’. This appealed to both the professional and hobbyist alike.

- The autochrome didn’t require any specialist equipment, it made it very popular with the hobbyist photographer, much to the dismay of the professionals who were concerned that amateurs would produce ‘the most appalling fried-egg results15’.

- The process handled red extremely well, creating a rich, romantic warmth in the red tones (but sometimes had problems portraying a correct blue and sometimes yellow). Many photographers took advantage of this trait and often used models who had rich red and auburn hair or introduced red elements such as shawls and parasols to increase the impact of colour in the images.

Women in Cofu, Auguste Léon – ladies in their national dress, showcasing how the Autochrome process enhanced the reds of their outfits

The launch

The launch was greeted rapturously and ‘many photographers were bewitched by the twin spells of depth and colour17’. Both Stieglitz and Steichen had been lucky enough to be in Paris when the Lumières launched the Autochrome and Stieglitz returned to America, declaring in a press release that ‘Colour Photography is an accomplished fact18’. He equated:

‘the marvels of “macronigraphing” (wireless telegraphy)…… to “looking at these unbelievable color photographs! … The Lumière process, imperfect as some may consider it, has actually brought color photography in to our homes for the first time, and in a beautifully ingenious, quick, and direct way19’ and he felt ‘the invention….. equaled that of photography itself in its importance20’.

Stieglitz prophesied:

“The possibilities of the process seem to be unlimited. Soon the world will be colour-mad – and Lumière will be responsible”21.

Other photographers

- Personnaz in France encouraged his contemporaries ‘not to leave it solely to our foreign colleagues to take advantage of this new progress in the very French art of photography22’.

- Steichen took plates to England and showed them to George Bernard Shaw, who ‘autochromed’ Alvin Langdon Coburn

- Coburn who ‘autochromed’ Shaw, actually travelled to Paris to get his own supply as they weren’t yet available on the British market.

- Steichen ‘though more taken than anyone with the latest vehicle of colour vision, kept his balance better than most…’ produced both larger and smaller plates and offered his autochromes at a wide range of prices23’.

- Newspapers printed several articles on colour photography

- Society of Colour Photography was established in London.

Untitled (Woman Posing in a Garden) Paul Bergon

Public exhibition

Despite the problems of public exhibition almost 100 autochromes appeared in the Salon Exhibition of 1908 (viewed against backlight, projected or viewed through diascopes), by figures such as Steichen de Meyer, Langdon Coburn and Annan.

‘many amateur photographers eagerly embraced the world of colour that was now finally, within their grasp24’.

Albert Kahn – banker and philanthropist

French banker and philanthropist Albert Kahn was also very excited by the possibilities of the Autochrome and ‘realised that photography was standing at the threshold of a new world of creative possibilities’25. He envisaged that it could be the ‘instrument that would help him achieve a cherished political ambition’26, to create world peace and promote international understanding through people experiencing the different cultures of the world.

Kahn’s Archive of the Planet – world peace through the Autochrome

Kahn considered the Autochrome to be an educational tool to broaden the mind through travel and set up a scholarship to allow teachers to visit various countries. He also ‘bankrolled’27 one of the most significant photographic archives in the world, his Archive of the Planet, now housed at the Musée de Albert-Kahn, France.

In 1908 he acquired his first autochrome plates and the images created were shot by his chauffeur Alfred Dutertre on a ’round the world’ tour that the pair undertook, thought to be the first known colour images of the respective countries that they visited.

Over the next twenty-two years, he sent photographers and cameramen all over the world, capturing film and still images, in colour and black and white. His photographers ‘recorded in intimate detail the lived experiences and cultural practices of thousands of ordinary people from across the globe28’ and immortalising the cultures at a time when often they were undergoing major political and social changes and upheaval.

Kitty Steiglitz, Alfred Steiglitz

What Kahn photographed

They travelled to the Western Front during World War 1, changing forever our black and white perception of the horror of the trenches. They chronicled the dying Gaelic villages of the Claddagh in Ireland, the mourning in Japan for the death of the Emperor and the changing face of the Middle East, Africa, Asia and Scandinavia.

Thanks to Kahn’s opérateurs we are introduced to the notables of the period, in glorious colour. Ramsay McDonald, Sir Austen Chamberlain, King Alexander 1 of Yugoslavia and the sculptor Auguste Rodin are all immortalised in autochrome plates.

Effects of the Wall Street Crash on Kahn & the Archive

Eventually, Kahn owned his own bank and probably thought he would be able to continue to finance the archive indefinitely. However the financial crisis of the Wall Street crash of 1929 ‘reduced one of the most successful bankers in Europe to something approaching penury29’ and by the mid-1930s he was bankrupt.

He sold his Boulogne estate to the local authority, but they allowed him to continue living there (it later became the Museum that housed the archive). The Archive survived the war, narrowly avoiding being stolen or destroyed when the Nazis invaded and now provides us with an amazing window on a time of change and social and cultural upheaval throughout the world and an Autochromic legacy of over 72,000 images.

Other uses for the Autochrome

As well as portraiture and historical and cultural documentation it was, like any new technology, used for pornography and nude studies due to its delicate handling of skin tones. Autochromes were also used as an educational tool (in the true sense, not Kahn’s sense).

A macro autochrome

Gervais Courtellement (one of Kahn’s Archive photographers) gave popular, illustrated lectures of his Oriental travels and opened a Palais de l’Autochrome which exhibited his war photos.

Aubert, one of Courtellement’s colleagues produced gory images when he worked in the war hospitals and some autochromes were used to document and examine various diseases, wounds and deformities, projected in lectures and in stereoscopes.

This provided a new way to share information with other hospitals and doctors. Dr Friedrich Paneth a chemistry lecturer and director of the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry in Mainz, was also an avid photographer and used autochromes in his lectures, projecting the Periodic Table from autochromes.

Book illustrations

Occasionally autochromes were also used to illustrate books if the publication had the finances to support the required separation to colour printing (not photographic printing). One such book the author of this essay discovered was The Adventures of Jack Rabbit by Richard Kearton, published by Cassell in 1911, which has six delicate autochromes reproduced in colour, showing a variety of woodland flowers, butterflies and moths, and bird’s eggs.

Vault of San Zeno de Maggiore, Fernand Colville, Archive of the Planet

After the initial excitment

After the initial excitement following the introduction of colour, photographers such as Stieglitz reduced their use of the autochrome because of the ‘lingering impracticalities30’of the process.

According to Natalie Bouloch, author of Autochromes and Pictorialism (in Impressionist Camera, Pictorial Photography in Europe, 1888-1918) Stieglitz et al, ‘deeply attached as they were to the idealistic doctrine of interpretation31’ came to the conclusion that autochromes were ‘mere slaves to reality32’ and came to see the autochrome ‘as part of a regressive movement33’.

Sales increased

Despite the limitations of the process and despite a ‘latent desire for colour photographs on paper34’, production and general sales increased. The British Journal of Photography at the time commented that ‘the demand in France has been so great that there has been no chance of any plates reaching England yet, but as the makers are doubling their output every three weeks it will not be long before plates can be obtained commercially in England35’.

Many photographers stockpiled plates, especially after the break in supply during World War 1 and Albert Kahn is thought to have purchased 1% of the total 20,000, 000 Lumière production and the process ‘dominated the market for colour photography for nearly 30 years36’.

Decline of the Autochrome

Endeavouring to resolve the issue of the fragility of the medium, in 1932 Lumière introduced the Autochrome on a film stock and marketed it under the name of Filmcolour and within two years it had almost totally replaced glass. However, these improvements failed to save the autochrome.

Competitors

Other manufacturers such as Kodak and Agfa were developing ‘new multi-layer colour films through subtractive synthesis – thus doing away with the need for filter screens37’. In 1935 Kodachrome was announced in the Rochester Evening Journal, as ‘the first commercially viable colour film38’ and it was described as ‘a momentous day in the history of colour photography39’. In 1938 National Geographic magazine used only sixty-two Kodachrome images, by the following year that had increased to three hundred and seven.

Very shortly after that, they decided to use Kodachrome exclusively both as 35mm and sheet cut film. In 1936 Agfa patented a method of producing colour couplers that ‘stayed put40’ in an emulsion layer and they were able to bring to the market a multilayer reversal film which they called ‘Neu’. It was also 35mm and slightly slower than Kodachrome.

And so the era of the autochrome was over.

End of an era

The process that promised so much and excited so many photographers, that had made such an invaluable contribution to the history of the photographic story, but which for some had failed to fulfil that promise, ceased to be a viable, commercial medium.

The question in respect of this essay, is whether it satisfied the quest of the photography community for the ‘Holy Grail’ of easy to use, commercially viable colour photography?

Was it inclusive?

Firstly one can ask whether the process allowed all members of the photographic community to produce colour images. The fact that all photographers could use their existing equipment, without having to buy bulky and pricey ‘add-ons’ would suggest that the autochrome was egalitarian enough to meet this first requirement.

Was it recognisable and permanent?

Secondly was the colour produced by the autochrome process recognisable and permanent? Unlike previous attempts to produce colour, the autochrome colours were rich, atmospheric and permanent (lasting, we now know over 100 years).

Although there were some issues with colour sensitivity and speed, these were addressed either through the use of filters or improved as the process was refined during manufacture. This suggests that the autochrome fulfilled the second requirement of colour photography.

Was it easy to view?

Next, was the process easy to handle and view? At first, the plates were very fragile, leading to many breakages and wastage, but this was later improved by using a film stock. Viewing and exhibition were problematic, requiring as it did, the use of projection or diascopes to make the most of the warmth of tones and the luminous quality inherent in the process. In this respect, the autochrome was not so successful and so it doesn’t fulfil the requirements fully.

Was it competitively priced?

As with any commercial product, price is always an issue. When they were first released onto the market plates were sold in boxes of four, rather than the usual twelve. This suggests that they were much more expensive than black and white plates and some photographers, after the initial excitement had died down, stopped using them for this reason. However, they fulfilled a ‘need’ in the photographic community, that of a viable colour medium and many used them despite the price. So I would suggest that on this point the autochrome fulfilled the requirement of commerciality.

Did they offer creative potential?

Black and white photography had allowed many photographers to ‘tweak’ and manipulate their work to create fine art and aesthetic images, not just direct reproductions of nature and people. Many professionals had hoped that the introduction of colour photography would allow them the same leeway, but unfortunately, they were to be disappointed, with only a few such as Steichen developing enough skill to manipulate the image during processing to satisfy his artistic desires.

Should this suggest that the autochrome was unsuccessful, just because a select few were disappointed? The fact that it allowed amateurs to produce colour images, which had previously been beyond their reach, suggests that in fact, it was extremely successful with general photographers.

Conclusion

Nanny Mary Warner with Lotte and Hans Kūhn – Heinrich Kūhn

Overall the autochrome process produced beautiful, atmospheric images of a period of great social and cultural change. It failed to fulfil the latent desire for prints, but proved to be an invaluable step in photographic history towards colour photography as we know it today, …

…..especially digital photography which uses Bayer technology, a mosaic colour filter system similar to the autochrome.

To view examples of Nicola’s colour photography click here

To discuss your photographic needs call 0775 341 3005 or email info @ iconiccreative.co.uk

Footnotes:

1 Autochrome: the Dawn of Colour Photography, National Media Museum, pg 1. (Article in Appendices). / A Century of Colour Photography from the Autochrome to the Digital Age, Roberts, Pamela, pg 25.

2 Autochromes: the Dawn of Colour Photography, National Media Museum, pg 1.

3 A Century of Colour Photography, Roberts, Pamela, pg 12

4 A Century of Colour Photography, Roberts, Pamela, pg 15

5 The Autochrome: 100 Years of Color Photography, Antman, Mark. Article reprinted from The Picture Professional, Issue 2, 2007 (Article in Appendices). Quote from Alvin Langdon Coburn in a letter to Alfred Steiglitz, pg4 of article.

6 The Autochrome: 100 Years of Color Photography, Antman, Mark. Article reprinted from The Picture Professional, Issue 2, 2007 (Article in Appendices), pg1

7 The Illustrated History of Colour Photography, Coote, Jack, pg40.

8 Autochromes by Clarence H. White, Nickel, Douglas R., Record of the Art Museum, Princeton University, Vol 51, No2, The Art of Pictorial Photography 1890-1925, pg2. (Article in Appendices).

9 The New Colour Photography – A Bit of History, Steiglitz on Photography, Steiglitz, Alfred, pg 208. (Article in Appendices).

10, 11, 12 A Century of Colour Photography, Roberts, Pamela, pg 24.

13 The Autochrome: 100 Years of Color Photography, Antman, Mark. Article reprinted from The Picture Professional, Issue 2, 2007 (Article in Appendices), pg1. (Article in Appendices).

14 Autochromes: The Dawn of Colour Photography, National Media Museum, pg2. (Article in Appendices).

15 Autochromes by Clarence H. White, Nickel, Douglas R., Record of the Art Museum, Princeton University, Vol 51, No2, The Art of Pictorial Photography 1890-1925, pg2. (Article in Appendices).

16 The Autochrome: 100 Years of Color Photography, Antman, Mark. Article reprinted from The Picture Professional, Issue 2, 2007 (Article in Appendices), pg1. (Article in Appendices).

17 Autochromes: The Dawn of Colour Photography, National Media Museum, pg3. (Article in Appendices).

18 Stieglitz A Beginning Light, Hoffman, Katherine, pg 243. Quoted from the original Press Released reproduced in the book.

19 Stieglitz A Beginning Light, Hoffman, Katherine, pg 243. Quoted by Hoffman from Stieglitz, 1907b, pp. 24, 25.

20 Autochromes by Clarence H White, Nickel, Douglas R., pg 1. (Article in Appendices).

21 The Wonderful World of Albert Kahn, Okuefuna, David, pg 9.

22 Impressionist Camera, Pictorial Photography in Europe, 1888-1918, Saint Louis Art Museum, pg 270. Quoted from A propos des autochromes, Bulletin de la Société Française de Photograhie no 18, 1908, p.378.

23 Edward Steichen: The Early Years, Metropolitan Museum of Art, pg 32.

24 Autochromes: The Dawn of Colour Photography, National Media Museum, pg 4. (Article in Appendices).

25, 26, 27 The Wonderful World of Albert Kahn, Okuefuna, David, pg 12-13.

28 The Wonderful World of Albert Kahn, Okuefuna, David, pg 12-13.

29 The Wonderful World of Albert Kahn, Okuefuna, David, pg 15.

30 Edward Steichen: The Early Years, Metropolitan Museum of Art, pg 32.

31, 32, 33 Impressionist Camera, Pictorial Photography in Europe, 1888-1918, pg 272.

34 The Illustrated History of Colour Photography, Coote, Jack H, pg 71.

35 The Illustrated History of Colour Photography, Coote, Jack H, pg 41.

36 Autochromes: The Dawn of Colour Photography, National Media Museum, pg 4.

37 Autochromes: The Dawn of Colour Photography, National media Museum, pg 4.

38 http://www.dailykos.com/storyonly/2006/12/7/04913/9030/204/278472

39 The Illustrated History of Colour Photography, Coote, Jack H, pg 141.

40 The Illustrated History of Colour Photography, Coote, Jack H, pg 152.

Reference

Hoffman, Katherine, Steiglitz, A Beginning Light, Yale University Press, New Haven and London.

Saint Louis Art Museum (essays by various authors), Impressionist Camera, Pictorial Photography in Europe, 1888-1918, Merrell, London and New York.

Coote, Jack H, The Illustrated History of Colour Photography, Fountain Press.

Nickel, Douglas R., Autochromes by Clarence H. White, Record of the Art Museum, Princeton University, Vol. 51. No. 2, the Art of Pictorial Photography 1890-1925, pp. 31-37, Princeton University Art Museum (article printed in Appendices).

National Media Museum, Autochromes: The Dawn of Colour Photography, National Media Museum (article printed in Appendices).

Steiglitz, Alfred, Steiglitz on Photography, Chapter: The New Colour Photography – A Bit of History, Aperture (article printed in Appendices).

Antman, Mark, The Autochrome: 100 Years of Color Photography, Reprinted from The Picture Professional, Issue 2, 2007 (article printed in Appendices).

Okuefuna, David, The Wonderful World of Albert Kahn, Colour Photographs from a Lost Age, BBC Books

http://www.dailykos.com/storyonly/2006/12/7/04913/9030/204/278472

Bibliography

Books and articles

Metropolitan Museum of Art, Edward Steichen, the Early Years, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Marien, Mary Warner, Photography A Cultural History, Laurence King Publishing.

National Media Museum, Alternative Photographic Resources, National Media Museum.

Friedman, J.S., History of Color Photography, Focus Press.

Roberts, Pamela, A Century of Colour Photography from the autochrome to the digital age, Andre Deutsche (article printed in Appendices).

Johnson, Frances Benjamin, An American Century of Photography, Hallmark

Online sources

http://www.photographymuseum.com/potatoestopictures.html

http://www.nationalmediamuseum.org.uk/autochrome/Notable_Photographers_detail.asp?PhotographersID=9

http://www.institut-lumiere.org/english/lumiere/autochrome.html

http://www.nationalmediamuseum.org.uk/autochrome/Colour_Development.asp

http://www.notesonphotographs.eastmanhouse.org/index.php?title=Osterman,_Mark._%22The_Autochrome_Process%22

http://users.telenet.be/autochromes/introduction.htm

http://www.luminous-lint.com/app/vexhibit/_THEME_Autochromes_Travel_01/2/0/0/

http://blog.photoshelter.com/2008/07/george-eastman-house-and-the-autochromes.html

http://blog.gettyimages.com/tag/autochromes/

http://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/autochromes.html

http://photography.nationalgeographic.com/photography/photographers/first-natural-color-photo.html

http://www.photographymuseum.com/autochromeclatworthy.html

DVDS

The Twenties in Colour: The Wonderful World of Albert Kahn, The End of a World, BBC4 Thursday 29th November 2007

Edwardians in Colour: The Wonderful World of Albert Kahn: Northern Exposure, BBC2 Friday 23rd November 2007

First of all I want to say terrific blog! I had a quick question in which I’d like to ask if you don’t mind. I was curious to find out how you center yourself and clear your mind prior to writing. I have had a difficult time clearing my mind in getting my thoughts out. I truly do take pleasure in writing however it just seems like the first 10 to 15 minutes tend to be wasted simply just trying to figure out how to begin. Any ideas or tips? Many thanks!| а

Thanks. A lot of what I write is spur of the moment stuff, so I have an idea and then think I must write a post about that. The Autochrome post was actually my final dissertation for my photography course so took a lot of research and work. Other pieces are part of various series, some of which I write spontaneously and other I plan, like the Top Ten heritage sites series.